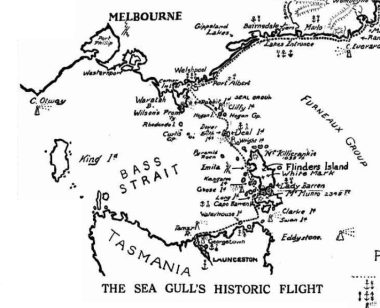

Flying boats were considered the most likely way a passenger service between Tasmania and the mainland would operate in the 1920s. Aerial surveys of the coastline were undertaken to identify suitable landing sites in the Furneaux group and along the Tasmanian coastline.

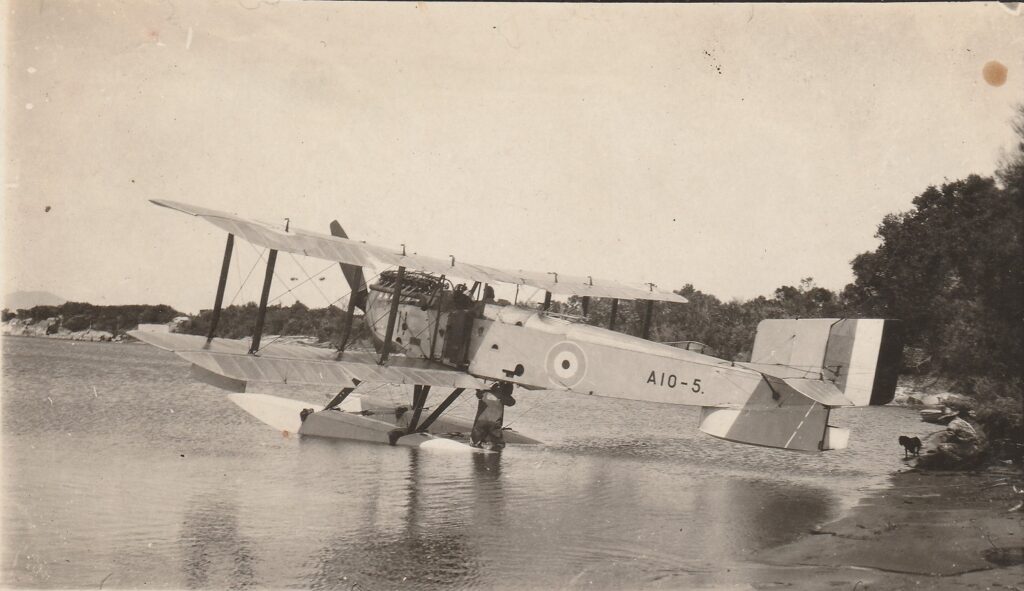

A ‘seaplane’ is a land plane equipped with floats. A ‘flying boat’ incorporates a boat into the fuselage and lands on water, while an ‘amphibian’ is a flying boat with additional landing wheels to allow it to also land on land.

1921

First Flying Boat to Cross Bass Strait – The Seagull

The first survey flight was conducted by a small wooden Curtis Seagull flying boat. The 2,700 km return trip from Sydney to Launceston took 36½ hours of flying over 16 weeks.

The flight was funded by the plane’s owner Lebbeus Hordern, a Sydney millionaire who had a strong interest in aviation.

Captain Andrew Lang was the pilot. A First World War pilot, he was also a journalist. Using the pseudonym Napier Lion, he wrote the Log of the Seagull, a series of 25 articles on the flight for The Sydney Mail newspaper.

The flight was supported by a 30-ton auxiliary yacht, Acielle. Repairs undertaken to this ship caused many delays.

They departed Sydney on 13 March 1921, returning on 4 July 1921. A month was spent in Launceston undertaking extensive maintenance on the plane and their support ship.

Photographs were taken and mooring places investigated. These were provided to the Department of Defence.

The underpowered plane flew at low altitudes and low speed. It was greatly impacted by any turbulence it encountered. With its open cockpit, flying to Tasmania and back in winter was a huge accomplishment.

This was the first flight from Sydney to Tasmania. The Seagull was also the first plane to visit Flinders and Deal Islands.

1924 & 1925

RAAF Seaplane Survey Flights

The RAAF flew two survey flights of the Furneaux Islands and the east coast of Tasmania with their Fairey IIID seaplanes.

The Fairey IIID was a two-seater biplane, introduced at the end of the First Work War. The majority produced were land planes, but some were also configured as a seaplane by adding floats.

In February 1924 a seaplane flew from Wilson’s Promontory across the Furneaux Islands and along the east coast of Tasmania. They landed at St. Helens for petrol, before continuing to Hobart, returning a week later along the same route.

The Tasmanian survey trip was a precursor to the much bigger a survey flight around the coastline of Australia in another Fairy IIID seaplane, a journey of 13,800 km, taking 44 day and 90 hours flying time.

A more detailed survey of the Furneaux Islands was undertaken by two seaplanes in October 1925. Captain Johnson of the Civil Aviation Branch was part of the survey team. Passing over Wilson’s Promontory they hit rain squalls and after suddenly dropping about 200 feet, Captain Johnson’s suitcase fell out of the plane and was lost!

On arrival they landed on Franklin Sound at Lady Barron, the same sheltered landing spot used by Captain Lang in the Seagull Flying Boat. For five days they undertook a detailed aerial survey of the Furneaux group.

Returning to Melbourne, a journey that was expected to take about 3 hours, their flight battled against strong head winds taking 6 ¼ hours.

![RAAF Southampton Flying Boat [Weekly Courier]](https://bassstraitflight.au/wp-content/uploads/2022/11/Seaplane-5.jpg)

1929

First Direct Mainland Flights to Hobart and on to Sydney

The first direct flights from Melbourne to Hobart and then to Sydney were by a RAAF Southampton flying boat.

The RAAF would periodically visit Tasmania on training flights and they were also used to promote the RAAF and drive recruitment.

In 1929, a RAAF Southampton flying boat was used to fly recruitment personnel from its Melbourne headquarters to interview candidates in Hobart, Sydney, and Brisbane. The 4,400 km trip was flown in 5 days.

The first leg was from Melbourne to Hobart on 21 February 1929. The direct flight took 4 hours and 45 minutes. This was the first direct flight from the mainland to Hobart.

They interviewed candidates on the following day.

Then on 23 February, they flew from Hobart to Sydney, a flight of 7 hours 50 minutes. Their route again was along the east coast of Tasmania until they were opposite St Mary, then they followed a course directly to Sydney. This was the first direct flight from Tasmania to Sydney.

Included in the RAAF interview team was Squadron Leader Raymond. Brownell. He was the Director of Personnel Services for the RAAF at the time.

Brownell was a Tasmanian. He enlisted in the AIF during the First World War, serving at Gallipoli and on the Western Front. In 1917 he transferred to the Royal Flying Corps and became a Flying Ace by shooting down 12 enemy aircraft. This was the highest number shot down by the seven Tasmanian Flying Aces in the First World War. Upon return to Australia, he joined the RAAF in 1921. He served in many senior positions until he retired with the rank of Air Commodore in 1947.

Extract from the ‘Log of the Seagull’

Lieut. Long describes his approach to Lady Barron on 16 May 1921 in a flight log that was published in the Sydney Mail newspaper.

As we passed Entrance Rock, the sky suddenly became dark, and with a violent bump we began to lose height like a lift. This lasted for a few seconds, when we got another upward push, and then the fun began in real earnest.

When we were well in the Sound, we found ourselves suddenly enveloped in an inky-black cloud that appeared to come from nowhere, and down had to go the throttle and the nose. Down, down we went. Then out into the open we once more flew, 1,200 feet off the water.

We were received with a colossal side bump which was at once converted into a stomach-moving flat drop. At first, I did not take too much notice of this, though one could not help realising that it was a bump out of the ordinary. There appeared to be no response from the engine. The accustomed roar seemed to have become muffled, though a glance at the rev. counter showed that I was all at sea, the revolutions varying from 1480 to 1600. This made me at once take an extra “feel” of the joystick, and from this there was no response. We still continued to drop. Taking a hasty glance shorewards, I was dumfounded to find that we were hardly making any forward speed at all. We seemed to have almost come to a standstill.

And then the water came rushing up like a racing car showing off. Just as my feet were on the very verge of leaving the rudder-bar, so as to double them up and lessen the impact when the crash came, the hull suddenly received a bump that shook her from stem to stern, and in the fraction of a second we were 100 feet up in the air again.

Just after receiving a terrific upward bump which drove us up about 75 feet, we ran into another downward drop, which once more took us almost down to water-level. Up again, a few seconds’ respite, and then down again. It was horrible.

Just ahead of us, after receiving an upward bump, five catspaws appeared on the surface of the water. It instinctively told me to look out, that there was something doing, and as we came over the spot, down she went with a nasty heel over to the starboard side.

This is what went on for fully fifteen minutes — one perpetual fight to keep the machine on a level keel, which, under the conditions, was an utter impossibility. One had to just grin and bear it. Though it was bad enough for the one who was in action, it was a hundred times worse for the poor unfortunate passenger.

Then suddenly the light appeared to fail, there was a blur over my goggles, and we were in a rainstorm. Whence it came we knew not, but it was on us without the least bit of warning.

For the next five minutes my glasses were being perpetually wiped. Happily, we came out as suddenly as we had run into the fracas; there was rough water twenty feet below us, and straight ahead was Lady Barron, with Vansittart Island on our starboard bow. We were still being bumped, but the attack had lost a great deal of its sting.

Nearing Lady Barron one could locate a little harbour. Just as I felt she was about to take the water we were suddenly attacked by a bump under the starboard wing tip; she reeled over to an angle of 45 degrees, and at the same time threw the nose right up into the air. The force was so great that it unseated me. With almost the speed of a trained boxer all my strength was exerted to push the joystick hard forward to the right. It was all over in a second. From an apparently hopeless position she suddenly came back to an even keel, and ten seconds later was at rest on the surface.

And so ended the most trying flight, without any exception, that has been experienced by me during the whole of my career as a pilot.